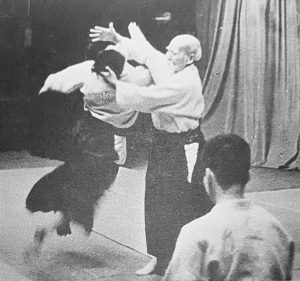

O’Sensei walks in

In recent times there has been much debate around training style and focus within the organisation. I will share with you how we trained in the early days and why I believe every practitioner should train this way for at least some part of their learning.

In recent times there has been much debate around training style and focus within the organisation. I will share with you how we trained in the early days and why I believe every practitioner should train this way for at least some part of their learning.

It is important to explain my current situation.

I live and work in a world of violence. There is no room for error nor can I have a bad day. Not only do I live in this world of violence, it is my occupation to teach people violence. To be effective in skills, definite in decision and morally and legally correct.

It is also my occupation to inoculate from stress (Warrington 2016) those I train.

How this occurs will be discussed later in the article.

I have chosen the word violence very carefully. Not to be provocative but it highlights that what we are actually doing in training.

The physical aspect of techniques require us be violent.

I would be interested in a person’s argument that striking, throwing, causing pain through joint manipulation and hitting a person with a piece of wood are not violent actions.

I do not accept that what we are doing when executing technique is anything less than violent.

Our approach and ethos around what we are doing is certainly not violent and here lays the paradox.

How can we train for violence of action but promote peace and harmony?

This debate could be the topic of its own article and I will not go into this at this time.

My personal belief is, that to not use violence, or only use violence when necessary, is to have an intimate knowledge of violence and your ability to impart violence.

I do not believe this makes a person violent.

In fact the opposite is true.

Knowing your ability to impart force provides awareness of the harm you can do. Knowing the effect of force on a person and the level of force you actually need to impart allows you to use only what is necessary on a person.

You become more effective and resolute in your technique as you need to do less, not more. You can strip away the mysticism and confusion of great technique. You therefore have less to think about and process. This leads to having a perception of more time to act and you become less reactive.

This awareness is affected by stress.

When a person is fearful or panicked they can use disproportionate force in the situation.

How can you say, honestly, that when you are confronted by the angry man, with no experience around your own responses and abilities in that situation, you will be effective?

You can’t.

Fighting Mind is destroyed by having this awareness.

There is no need to slam a person into the mat or put all my weight behind a cut. A person would get hurt. You are able to dial up and down the effect on uke if you know both ends of the scale. You are able to feel that you have enough torque on uke and can back it off so they can roll.

Without knowing both ends of the scale how can you know your true ability?

Over time this can be applied to an off mat situation. You see an opening or feel the attacker off balance and modify this to use only what is required.

I am not stating you need to have first-hand experience with violence or competition.

But this leads us to question- what is your personal experience with violence?

And what is your ability to impart violence?

I will ask you to search your own experiences of violence and examine how you responded. Being placed in an actual confrontation is confronting, hence the name.

How did you manage the stress? Have you even thought about how to manage stress in a confrontation? What effect will stress have on your technique?

If you think you won’t be affected by stress, or your technique will stack up in the big bad world you can stop reading now.

Thank you for your time.

Those who have kept reading I would remind you that time on the mat does not directly correlate to proficiency of technique or the ability to manage stress.

Those who believe they can overlook stress are dangerous. Also very dangerous and misguided is the notion that because I’ve study an art for long time you are therefore more skilful.

This is driven more by ego than reality.

There are some people who are more skilful and engaged in the art after 12 months than some practitioners who have studied 12 years.

My experiences of violence are varied. From working in the security industry, law enforcement and on the mat. Having applied my art off the mat in a variety of situations, I can say that if I had not had the experience of the early days of training I would not have fared so well.

It was in those times that we trained and trained and trained. These were long and hard days that left as gasping for breath and near to true exhaustion.

So what did we do in the early days?

We were is a great position that can’t be denied.

Being able to devote around 5-6 hours a day on the physical aspects alone is not a position many people have the opportunity to do nor the desire to experience. Being students with access to a great facility for really no cost did make things easier. To be honest, in the early days I was a sceptic. I was not convinced what I was seeing could work. I am no longer a sceptic.

Most of the training was around the physical execution of techniques. Nothing was off the table.

There was a real sense that we were in some ways trying to defeat the techniques and find fault with them.

Nothing was sacred. It couldn’t be. We trained with a variety of other people. All of whom were and are very accomplished in their own arts.(ie, other great martial artists NOT from an Aikido background)

We never shied away from them and in some cases made them converts.

Another long-time friend of mine who was world class karate practitioner often commented on what we were doing and could easily draw comparison with his own art. He saw first-hand what happened in the dojo translated to the ‘angry man’. He took some techniques and used them in his own world with great success.

Techniques were unpacked and rebuilt constantly. This was done at a low level to ensure we had what we needed. Once we believed we had a workable technique we set about setting it as a conditioned response. Please don’t ever say the words muscle memory to me.

We were and still are not afraid to completely relearn and unpack a technique in the pursuit of effectiveness.

I recall cutting with a bokken thousands of times. Getting the technique aspects perfect. Really focusing on what is means to have correct form and how that relates to power. Did I mentioned we were all previously highly competitive sports people? We understood the need to have perfect form and how that related to power generation. The greatest sports icons generate power effortlessly. Why? Form and repetition! Jordan didn’t pick up a basketball suddenly become the greatest player in the world. Schwarzenegger didn’t walk into a gym and suddenly look the way he did. Hours, week, months, years, decades of relentless improvement. Seeking perfect form.

Never settling for mediocrity.

I will suggest you all read a book called Relentless by Tim S Grover.

Once this was correct we needed to see if we could take that isolated skill and apply it in the dynamic situation. The use of Shinai allowed us to test each other in a way that was safe and came as close to reality as we could get. I lost more than I won.

What existed, and still does, is the acceptance of failure.

No one was fearful of failure.

We actually sought it out.

We wanted to test our ability to the point where we could say “I failed” rather than ‘I don’t think I can go on?” There was no shame in failure, only knowledge. Can we do this technique this way? No we can’t because……..

This happened constantly. Why didn’t things work? What do I need to fix?

Ah, I need to be strong here, soft here, cut here not there. We also worked with immediate feedback.

Meaning, if you were open you got punched, off balance you got thrown, no rotation in ukemi your thigh was bruised from hip to knee.

This level of physical execution could only occur after we could all take Ukemi to a high level.

We didn’t talk about the need to break fall. Nage made us break fall.

Yes, nage is responsible for the break fall not uke.

I will also mentioned that those who trained in the early day were physically fit. We all played representative sport at some level. Not only did this give us the physical ability to train the way we did, it also bought with it the mental toughness to keep going and an understanding of the biomechanics of the human body.

Apart from bumps and bruises our group sustained no major injuries when training together. Preparing for the first seminar in Byron Bay was difficult and rewarding. Pushing our bodies to the point of exhaustion taught me a lot about myself. To get through the training I needed to make movements as economical as possible. This included techniques and ukemi. Remaining stable during techniques at hour 5 meant that when I wasn’t fatigued in hour 1 tomorrow I could perceive and analysis my techniques and improve.

It is my belief you need to be physically strong to practice any art. There are varying degrees of fitness but this is something that anyone can improve. Age, gender, current situation and work and time restrictions are weak excuses.

The stronger and more stable you are the easier it is to learn and train.

This is the process of Tanren.

Not flitting about the mat for 2 hours not breaking a sweat and engaging in Talkido.

This brings me to the title of the article.

What would O’Sensei say if he walked into the dojo and saw you training?

Would he see the real spirit of Budo that we are all trying to find? Or would he simply walk away? Would he smile and say they are searching?

What I see on a lot of classes and demonstrations is a mockery of the art. Dancing, paired movements with no sense of budo other than they take place in a dojo.

This is not Budo and this is not Aikido.

Demonstration have become more about dojo promotion than the promotion of the true essence of the art.

So where is the proof that this type of training is effective and in my opinion essential to your art? Simple.

I look at technique of all those who trained in a similar fashion and evidence is overwhelming.

What this has meant for me is that I have been able to strip away a lot of complexity. Learning new techniques or more importantly rebuilding a technique I don’t have to worry so much about balance, stability or fatiguing before I can condition the technique.

Those who are forged are always stable, always effective and unyielding.

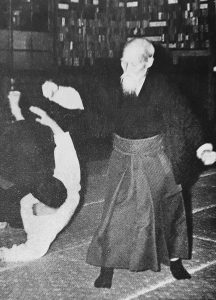

I look at photo and videos of O’Sensei and the masters and they certainly are. There is no need for them to be aggressive as they can use less force and less complex techniques to be effective.

Are you confronted by the effectiveness of their ability or are you confronted by yours in relation to what you see?

As part of by occupation I need to deal with people using 100% effort. There is no margin for error. I must protect myself which allows me to protect them. I get hurt I can lose my livelihood. They get hurt I can lose my livelihood.

This is truth, and truth can either cut you to the core, or set you free. Does the face staring back at you from the mirror rest easy in the knowledge that it has done all it possible can to understand all aspects of violence, training and the art you represent? Or does the face turn away in the knowledge that words and deeds are not the same thing? That talking a good fight has no relation to fighting the good fight? I know what my mirror says to me…..